The case for toning down your claims to delivering business benefits

A very short history of “features vs benefits”

To start off, I want to make clear that I think it’s excellent advice. Here’s the thinking behind it:

Traditionally, tech companies, and especially those with techie founders, tend to focus on product features in their messaging. And while features are one of the most obvious ways to differentiate from the competition, leading with them in marketing comms brings a whole raft of problems:

- Budget: The only people who quickly understand (and most naturally care about!) a feature are other techies: engineers with deep domain expertise. They are not usually the people with the budget who make purchasing decisions (but they may be important influencers)

- Relevance: The people who do have the budget are rarely deep subject matter experts – they need help understanding why a feature matters, and why they should care about it. They need it framed as a benefit to avoid a “so what?” reaction

- Readiness: At an early stage in the sales cycle – when buyers are gathering information and educating themselves – it’s usually too early to talk differentiation on features. The problem at this stage is winning trust by showing you understand your buyers’ world, and articulating the problem you solve for them (such as delays, or error rates, and their impact on the business). Your marketing job at this stage isn’t to sell – it’s to convince the buyer that they need a solution in the first place. It’s only at a later stage that you’ll show them that your solution is different, and better.

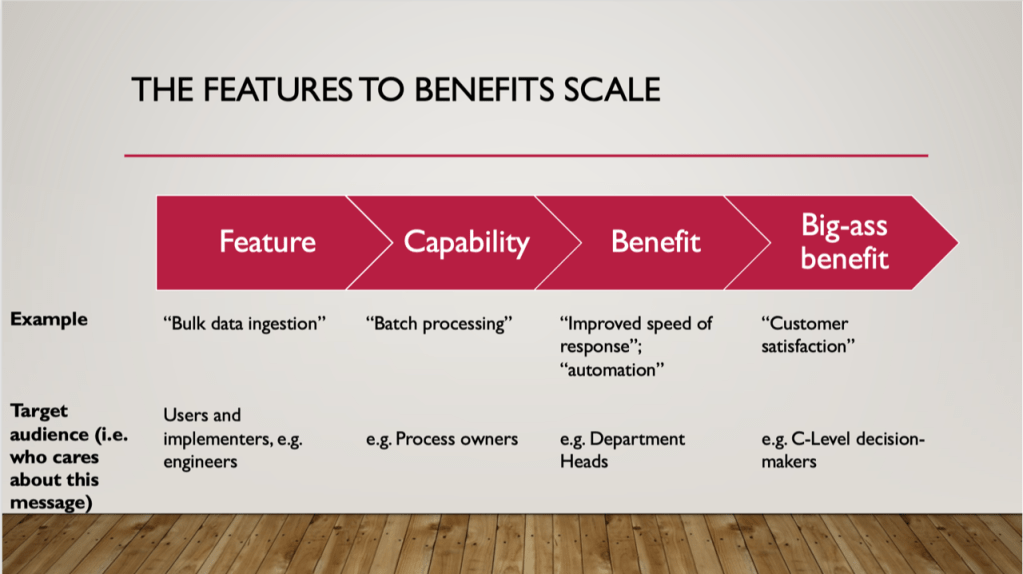

So that’s, roughly, where this best-practice advice comes from: to help techie people frame their product as a business solution rather than a technological one. And to show why your solution matters to more people than just its techie users. That’s why, in messaging frameworks, you often see diagrams like this, that ladder up features to benefits (and align them to buyer personas):

The credibility issue

One of the key strengths of this approach has to do with credibility: buyers don’t generally question a vendor’s ability to deliver on a feature, but they may be highly sceptical of lofty claims to a big-ass business benefit (or BABBs, as I lovingly call them). So showing how a feature ladders up to a benefit is a good way to give substance to your claim.

But, I wouldn’t be me if I didn’t have some reservations about the validity of this as universal best practice. As I said above, I don’t think this advice is for everyone.

The case for modesty

I believe that for a significant number of tech vendors and their products (and especially slick digitally-first startups that haven’t been founded by techies), it pays to be modest: first of all, because claims can be tenuous if not backed up by really solid data (eg “improved customer experience” means nothing if you don’t have the NPS score or something similar to prove it); and secondly, the higher you aim with your BABB (e.g. “Competitive Advantage”), the more abstract you become – and risk claiming everything, and therefore nothing at all. So you need to decide which sort of selling personality you want associated with your brand: data-driven or visionary (I’ll write something about this soon).

And I can think of a few concrete cases when your messaging definitely shouldn’t go all the way to C-Level benefits:

- When the C-Suite isn’t part of the purchasing decision. I know many clients don’t like to hear this (everyone wants to target the CEO these days!), but be realistic: if you’re not selling mission-critical enterprise systems that can seriously claim strategic relevance, you may have to accept that the CEO will never know that you and your product exist. They may completely delegate the buying process to their IT, user, and procurement departments and ultimately only sign off on the purchase.

- When you sales team can’t deliver the story: Features-to-benefits messaging is about getting the altitude right and understanding the complexity and nuances of each department involved. A really great sales person can tell the right story to each customer persona AND connect it all to a big business goal, too. It’s a rare skill and not all sales teams can deliver on it. If they can’t, aiming for something like “competitive advantage” in your messaging is likely to feel like overclaim or fluff to your prospects.

- When you’re in danger of neglecting the core buyer. It’s usually not a good idea to approach an engineer with a big business vision (unless they’re the sort of ambitious go-getter every marketer hopes for but rarely encounters); just like you’re likely to bore a CEO stiff with talk about APIs. On a recent project I worked on, the core buyer was a Head of Digitalisation for HR. As I interviewed them about their challenges, I kept probing for things like “retention rates” and “employee satisfaction”, but they kept talking about inefficient processes. The lesson: If I were to try to sell anything to this person, I’d have to frame it in terms of process improvement, not something bigger and more abstract – or I’d probably lose their interest.

Focus on your best prospect and empower them instead

In all of these cases, it’s a much better strategy to optimise your messaging for your core buyer persona (e.g. the department head) and focus on the benefits and KPIs they care about. I’d recommend having your C-level messages in the back pocket and bringing them up in one-on-one sales conversations rather than in your marketing materials.

And: it’s always a good idea to create a piece of content that enables your champions to sell internally – such as

- An overview of talking points broken down by buyer group functions

- A business case template

- An interactive ROI calculator

Or maybe they’ll ask you for a specific format they know their decision-maker will like. Indulge them and have your marketers fix one up. Having an internal champion deliver your message in your stead to the C-Level is usually much more successful than a direct sales pitch.

TL;DR: stay modest, retain credibility, remain relevant

I want to emphasise that modesty is different from lack of confidence: as a tech brand and product, you should definitely know where you play and confidently claim your space in your market. That includes knowing how you can drive business success for your customers.

But in many cases, the real skill is identifying the core decision-maker first (hint: it’s probably not the CEO!), then aligning your claims to their goals and KPIs. When you do that, good things will happen:

- You’ll speak to their needs and pain points

- You’ll credibly show how your solution makes their life easier

- You’ll demonstrate how you can positively impact the KPIs they themselves are measured on

- You’ll forge a more natural and credible path to the decisoino-makers

By convincing the key person thoroughly rather than doing a half-arsed job across the board, you ultimately stand a much better chance of selling. This is quiet confidence and it goes a long way.